News

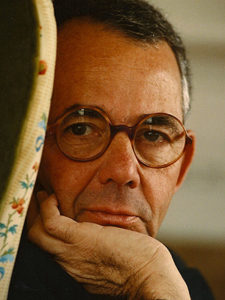

Homophobic Author Fears ‘Noted Homophobe’ Will Be Carved on His Gravestone

Essayist Joseph Epstein has recently expressed the fear that “Noted Homophobe” will be carved on his gravestone. The fear is not without justification.

As he nears the age of 80, essayist Joseph Epstein has recently revealed that he fears that what will be carved on his gravestone are the words “Noted Homophobe.” The fear is not without warrant, for his long and productive career has been shadowed by persistent charges of homophobia.

Obviously, Epstein would prefer to be remembered as a distinguished man of letters. He has credentials to claim such a sobriquet, though they are somewhat less compelling than one might think, considering that he has published more than 20 books.

He taught in the English Department at Northwestern University for almost 40 years, but while he possesses an impressive cache of erudition, and was apparently a popular teacher, he never earned a Ph.D. and has published no original scholarship.

He has written some fiction and for many years edited the Phi Beta Kappa magazine, The American Scholar, but he is not distinguished as either a creative writer or editor. Most of his books are either lightweight, gossipy musings on topics such as snobbery or ambition or friendship or they are collections of essays originally published in magazines.

As an essayist, he has earned acclaim in some circles. He has even been–preposterously, in my view–described as one of America’s greatest essayists. His essays cover a wide variety of subjects, and are uneven in quality; and not everyone appreciates either the predictably right-wing talking points expressed in most of them or the arch and condescending style in which they are typically composed. Although he has written some impressive essays, mainly on literary subjects, a great deal of his prodigious output is, alas, hack work.

Homo/Hetero

Epstein’s reputation for homophobia rests principally but by no means exclusively on a notorious essay published in Harper’s Magazine in September 1970, ““Homo/Hetero: The Struggle for Sexual Identity.””

A rambling, often incoherent, highly subjective meditation on homosexuality, the essay, for all its flaws, exhibits an energy absent from most of Epstein’s work, which probably indicates that it is deeply felt and expresses honest (though repugnant) emotion.

In it, the author, in the hyperventilating hyperbole of an Old Testament prophet, portrays gay people as a doomed, utterly foreign “other.”

“They are different from the rest of us. Homosexuals are different, moreover, in a way that cuts deeper than other kinds of human differences–religious, class, racial–in a way that is, somehow, more fundamental. Cursed without clear cause, afflicted without apparent cure, they are an affront to our rationality, living evidence of our despair of ever finding a sensible, an explainable, design to the world.”

Among the most objectionable remarks in the 10,000-word polemic is Epstein’s solemn declaration that “If I had the power to do so, I would wish homosexuality off the face of the earth.” He went on to explain, “I would do so because I think that it brings infinitely more pain than pleasure to those who are forced to live with it, because I think there is no resolution for this pain in our lifetimes.”

He also confessed, “There is much that my four sons can do in their lives that might cause me anguish, that might outrage me, that might make [me] ashamed of them and of myself as their father. But nothing they could ever do would make me sadder than if any of them were to become homosexual. For then I should know them condemned to a permanent niggerdom among men, their lives, whatever adjustment they might make to their condition, to be lived out as part of the pain of the earth.”

Reaction

The article, published only a year after the Stonewall riots, sparked a great deal of indignation and anguish on the part of gay readers and prompted a famous sit-in at the offices of Harper’s Magazine on October 27, 1970 by members of the recently formed Gay Activists Alliance. The sit-in is often considered an important moment in the early gay liberation movement.

The most positive result of the irresponsible publication of Epstein’s ugly phillipic was that it stirred author Merle Miller, who had himself once been an editor at Harper’s, to come out publicly. He declared over lunch with some New York Times colleagues, “Look, goddamn it, I’m homosexual, and most of my best friends are Jewish homosexuals, and some of my best friends are black homosexuals, and I am sick and tired of reading and hearing such goddamn demeaning bullshit about me and my friends.”

More than that, he agreed–with understandable trepidation–to counter Epstein’s piece with an article for the New York Times Magazine.

Miller’s article, “What It Means to Be a Homosexual,” was published on January 17, 1971. In it, Miller detailed his life-long struggle with his sexuality, and explained the difficulties of coming to terms with one’s sexual orientation in an exceedingly hostile social environment. “I dislike being despised,” he wrote, “unless I have done something despicable, realizing that the simple fact of being homosexual is all by itself despicable to many people, maybe, as Mr. Epstein says, to everybody who is straight.”

Miller’s humane and heartfelt article was, as Craig Kaczorowski has noted, “a landmark piece of journalism,” one of the most widely read essays of the decade. The New York Times received over two thousand letters in response–more than the newspaper had ever received for a single article. Fueled by the anger Epstein’s essay aroused in him, Miller’s article was, as Emily Greenhouse observed, in its most basic sense a response to the bullying embodied in “Homo/Hetero.”

Miller’s essay was expanded and published later in 1971 as a bestselling book, the groundbreaking On Being Different: What it Means to Be a Homosexual. In 2012, Penguin Classics republished On Being Different with a foreword by Dan Savage and an afterword by Charles Kaiser.

(Dan Savage discusses On Being Different here).

The republication of On Being Different brought new attention to the odious essay that inspired it, and that may have prompted Epstein’s concern that on his gravestone would be carved “Noted Homophobe.” In a brief piece called “Go Google Yourself,” which was published soon after the reissue of Miller’s book, Epstein revealed that in Internet comments he had recently been called such epithets as “hack,” “deeply biased,” “bigot,” and “homophobe.”

“Homo/Hetero” was also excoriated by such writers as Gore Vidal in his 1979 essay “Sex Is Politics” and David Ehrenstein in his 2002 review article “Sexual Snobbery: The Texture of Joseph Epstein.”

But as a Daily Kos posting in 2012 pointed out, Epstein largely received a “free pass” for the genocidal homphobia expressed in “Homo/Hetero” as he blithely proceeded onto a successful career in publishing.

It is doubtful that a writer who proclaimed a wish in 1970 that any other group of people than gays be eradicated from the face of the earth would remain welcome in the mainstream media. However, Epstein’s “fag-baiting” probably aided his career as he moved more and more into the neo-con circle of Norman Podhoretz and his wife Midge Decter. Decter, Epstein’s editor at Harper’s and the chief defender of “Homo/Hetero,” would go on to publish her own notoriously homophobic essay, the despicable Commentary article “The Boys on the Beach” (1980), which Vidal brilliantly eviscerated in his 1981 essay “Some Jews and the Gays.”

History of Dissembling

As Paul Morton has noted, “Epstein never discounted his essay. He never gave a full-throated defense of it either. Most of his voluminous magazine work has been reprinted in book-length collections. ‘Homo/Hetero,’ whether due to his own or his various publishers’ preferences, has not.”

Epstein has referred in print to the essay on only a few occasions, and in them he blatantly mischaracterizes it and implies that others have misunderstood or misrepresented it. Cumulatively, these references constitute a tepid kind of apology along the lines of “I’m sorry if you have taken offense at something I didn’t say.”

In 2002, for example, Epstein acknowledged in an interview with Tim Rutten in the Los Angeles Times that “Homo/Hetero” is “an essay that has followed me around.”

He insisted, however, that “It was not meant to be an attack.” Rather, he alleged, the problem with the essay was not its content but the politicized reaction of readers: “in 1970, the subject of sexuality suddenly became politicized. Once that happens, all textured thinking goes out the window.” He added, somewhat plaintively, “I hope I don’t have a reputation as a homophobe, which is really a stupid word.”

Epstein’s fullest discussions of the essay came in 1985 and 2015, but they are buried in the midst of discussions in which he tellingly casts himself as a victim of political correctness, apparently seeking pity for having been maligned by “professional gay liberationists.”

In a 1985 New York Times Magazine essay entitled “True Virtue, in which he attacks “virtucrats” (i.e., those liberals who believe in their own moral superiority), he recounts an incident in which a reporter for Northwestern University’s student newspaper allegedly telephoned him to ask whether it was true “that you once said that you’d rather your sons be murderers or dope addicts than homosexuals.”

In response, he claimed that he could not after 15 years “recall all that I had written in that essay,” but described its argument in terms that bear little resemblance to the actual work. Epstein in 1985 pretends that “Homo/Hetero,” the tortured exploration of his own fevered attitudes toward homosexuality, was merely a dispassionate study arguing the unexceptionable premises “that the origins of homosexuality remain for the most part a mystery; [and] that, with the exception of a small number of extraordinary people, homosexuality has brought much grief to its practitioners.”

Despite his faulty recall, he indignantly told the reporter, he “was, nonetheless, quite certain that I could not have said that I would rather have my sons be murderers or dope addicts than homosexuals, and this for a simple reason: I believe no such thing, nor have I ever believed it.”

Although in fact the reporter’s description of what Epstein said in the essay is far more accurate than Epstein’s misleading characterization, he goes on to make an implied threat against her: ”I am fairly certain that I never said any such thing,” he tells her, and adds, chillingly, “. . . I would be grateful to you if you didn’t print that I did, unless you find proof of my having done so. I hope you will consider very carefully before you do such a thing.”

Epstein apparently believes that the anecdote illustrates how he has been victimized by an aggressive reporter who carries with her “the stink of virtue” and is drunk on her sense of moral superiority. Actually, however, it reveals him bullying a young woman who asked a perfectly legitimate question.

Surely it is a fair (if not inevitable) inference that a man who has written that “nothing [his sons] could ever do would make me sadder than if any of them were to become homosexual” would rather have his sons be murderers or dope addicts than to be gay.

I suspect that the incident never occurred, or at least did not occur the way Epstein reports. Rather, the anecdote is likely fabricated or embellished in order to allow Epstein to respond to his critics and to rewrite the history of the dicey essay that has shadowed his reputation all these years. He makes the essay sound so dull that very few people who did not already know of it would make the effort to find it and read it.

In his 2015 essay entitled “The Unassailable Virtue of Victims,” another screed attacking political correctness and affirmative action, Epstein again portrays himself as a victim.

This time he describes “Homo/Hetero” as a benign, even sympathetic, consideration of the problems faced by gay people: “In 1970, some 45 years ago, I wrote an essay in Harper’s on the subject of homosexuality. The chief points of my essay were that no one had a true understanding of the origins of human homosexuality, that there was much false tolerance on the part of some people toward homosexuals; that for many reasons homosexuality could be a tough card to have drawn in life; and that given a choice, owing to the complications of homosexual life, most people would prefer their children to be heterosexual.”

This description of “Homo/Hetero” cannot but be a deliberate prevarication, designed to obfuscate rather than to clarify. The essay is anything but a sympathetic account of the difficulties faced by gay people. Rather, it is primarily an exploration of the author’s deep-seated repulsion at the very idea of two men having sex.

Indeed, in “Homo/Hetero” Epstein asks, “Why can’t I come to terms with it?” He posits all sorts of reasons for his repulsion, including fear of the latent homosexuality in himself and a possible envy of homosexuals’ alleged evasion of responsibility. He admits finally, with an honesty utterly foreign to his 2015 prevarication, “I cannot get over the brutally simple fact that two men make love to each other.” This statement is not only the very thesis of the essay, but it is also practically a textbook definition of homophobia as a psychological condition.

Not content with simply lying about the 1970 essay itself, in 2015 Epstein then proceeds to whine about how “Homo/Hetero” has negatively affected his reputation: “Quotations from that essay today occupy the center of my Wikipedia entry,” he complains bitterly. “In every history of gay life in America the essay has a prominent place. When I write something controversial, this essay is brought up, usually by the same professional gay liberationists, to be used against me.”

He adds: “That I am pleased the tolerance for homosexuality has widened in America and elsewhere, that in some respects my own aesthetic sensibility favors much homosexual artistic production (Cavafy, Proust, Auden), cuts neither ice nor slack. My only hope now is that, on my gravestone, the words Noted Homophobe aren’t carved.”

Inasmuch as Epstein had not heretofore ever given any indication of having taken any pleasure that “tolerance for homosexuality has widened,” and, as far as I know, never himself did anything to promote tolerance for gay people, it is startling that he would think that his newly alleged support for tolerance should cut either ice or slack.

Homophobia at The American Scholar

In fact, “homo-unease,” as critic Jeet Heer has characterized Epstein’s approach to gay writers such as E.M. Forster, has been a hallmark of his entire career, whether in his snide condescension to writers or in his self-proclaimed antipathy toward gay and lesbian studies.

Indeed, he has boasted that during his long tenure as editor of The American Scholar, from 1974 to 1998, during an era in which gay and lesbian studies came to maturity within the academy, he published not a single article about the field. Moreover, as editor he ostentatiously refused to allow authors even to use the word “gay,” insisting instead on the more clinical “homosexual” to refer to gay people.

Epstein was eventually fired as editor of The American Scholar. Not surprisingly, in his account of his firing, he yet again portrays himself as a victim of political correctness, of “not being sufficiently politically correct.” It is true that many members of Phi Beta Kappa complained repeatedly of his disdain for gay and lesbian studies, women’s studies, Black studies, and other progressive trends in the academy, as well as of his ban on the word “gay.”

These complaints no doubt influenced his firing, and justifiably so. But inasmuch as the readership of the journal plummeted from more than 40,000 at the beginning of his tenure to fewer than 25,000 readers (with an average age of 55) when he was removed, I suspect that the loss of readership, along with his inability to attract younger readers, probably also contributed to the decision to replace him.

In any case, Epstein’s prejudices severely limited his effectiveness as editor of a journal devoted to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “ideals of independent thinking, self-knowledge, and a commitment to the affairs of the world as well as to books, history, and science.”

Conclusion

There is a great deal of irony that Epstein, who sneers at President Obama as an “affirmative action president” and regularly ridicules a “culture of victimhood,” nevertheless so consistently portrays himself as a victim. His credibility as a critic of the culture of victimhood is about as strong as Bristol Palin’s credibility as a spokesperson for abstinence.

In a 1989 essay entitled “The Joys of Victimhood,” however, Epstein did say something pertinent, or at least something that is certainly applicable to himself: “People who count and call themselves victims never blame themselves for their condition.” For all his whining about how he has been victimized as a result of being labeled a homophobe, it never seems to occur to him that he has only himself to blame.

Although I have no idea whether Epstein has actively fought against equal rights for gay people (or simply supported Republican politicians who did), his assumption of the mantle of victimhood for himself actually connects him not with the groups he routinely mocks for their purported obsession with the wrongs they have suffered–Blacks, gays, women, Latinos, the handicapped, et al.–but with the homophobes who fought so hard against marriage equality.

They too have a penchant for portraying themselves as victims of gay bullies and of a changing society in which they are often seen as bigots and haters. Like Epstein, they view themselves as victims of “political correctness” because their beliefs in the innate inferiority and “otherness” of gay people are no longer considered acceptable in polite society.

The claim of being persecuted for not being sufficiently politically correct is a familiar tactic of right-wingers, who want to escape criticism for their racist, anti-feminist, or homophobic speech and beliefs. It is an attempt to divert attention from the actual substance of an issue or event. Rather than acknowledging the wrongs they have afflicted on others, they wrap themselves in the mantle of the persecuted and pretend that they are the ones who have been mistreated.

Just as faux patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel, so whining about the burdens of political correctness is the standard complaint of the racist, the misogynist, and the homophobe.

I do not know how Epstein will be remembered or what will be carved on his gravestone. But I find his predicament in regard to “Homo/Hetero” both satisfying in a karmic sense–as a fitting punishment for a particularly cruel act that hurt a great number of people–and profoundly sad because it was entirely self-inflicted and could have easily been remedied had Epstein been a different kind of person, one less paralyzed by his sexual insecurities and more empathetic toward others.

Even now, if Epstein really wanted to escape the scarlet H of homophobe, he could forthrightly apologize for the damage that “Homo/Hetero” did and cease misrepresenting it as something other than it is.

Ultimately, Joseph Epstein is a sad case, not because he may suffer the indignity of being described as a “Noted Homophobe” on his gravestone or anywhere else, but because he lacks the insight and courage to accept responsibility for his own actions.

Enjoy this piece?

… then let us make a small request. The New Civil Rights Movement depends on readers like you to meet our ongoing expenses and continue producing quality progressive journalism. Three Silicon Valley giants consume 70 percent of all online advertising dollars, so we need your help to continue doing what we do.

NCRM is independent. You won’t find mainstream media bias here. From unflinching coverage of religious extremism, to spotlighting efforts to roll back our rights, NCRM continues to speak truth to power. America needs independent voices like NCRM to be sure no one is forgotten.

Every reader contribution, whatever the amount, makes a tremendous difference. Help ensure NCRM remains independent long into the future. Support progressive journalism with a one-time contribution to NCRM, or click here to become a subscriber. Thank you. Click here to donate by check.

|